We Are Unbelievably Sorry, But This Post Is For

Members

Want the full experience? Unlock all our premium content—including deep dives, exclusives, and more—by joining The Looth Group on Patreon.

If you have questions about membership, please email ian.davlin@gmail.com

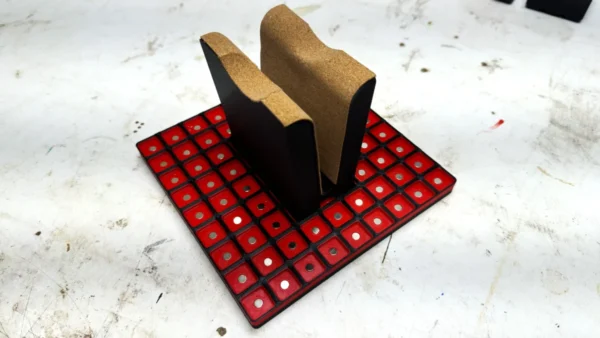

The Gurian Pinned Neck Joint Neck Reset

Responses

Awesome, I always wondered about the special tool needed for these. I had heard about them for years. This is amazing info, not that I’m excited to do one 🙂 ! But I’d choose one these any day over a Guild! 🙂

Hey Dave, I did not know the article was online already, just finished it yesterday. Well there is certainly a lot less glue on them than a Guild which are known for excess adhesives in the dovetail.

@patreon_112385373 I’m sorry, I thought I let you know that it was live.

That is so cool! Thanks for sharing the ideas.

The first time if reset the neck on the Gurian I snapped on of the pegs trying to man handle it out….. This is much more elegant!

Aww, this is so cool! And so forward thinking! Designing repair elements into the process as a forethought instead of afterthought.

Perfect just what i was looking for Thanks!!

You’re Welcome Peter, pd